Introduction

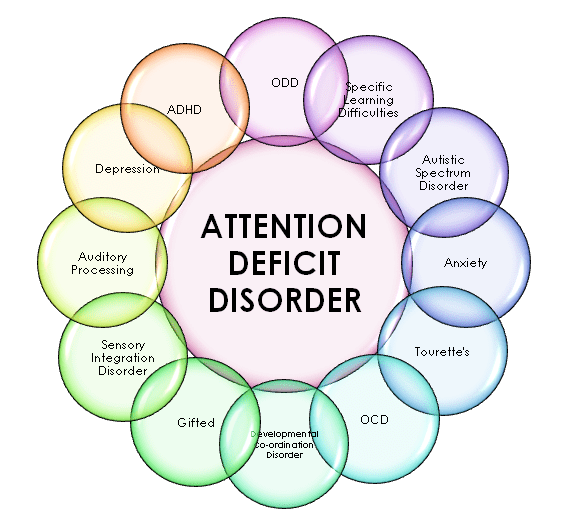

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is the neurodevelopmental disorder which is defined by executive dysfunction leading to excessive and pervasive signs such as inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, and emotional dysregulation that are developmental inappropriate and impairing in multiple contexts. Executive dysfunction is the underlying cause of ADHD symptoms, and dysregulation of emotions is frequently regarded as a primary symptom. Impaired time management, inhibition, and sustained attention are examples of self-regulation issues that can lead to poor work performance, relationship problems, and a host of health risks.

These factors combined can predispose people to a lower quality of life and a 13-year decrease in life expectancy on average. In addition to non-psychiatric diseases, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is linked to various neurodevelopmental and mental problems that may exacerbate existing impairment. A chronic pattern of hyperactivity-impulsivity and inattention that impedes functioning or growth, as demonstrated by (1) and (2):

(1) Inattention

At least six months’ worth of six (or more) of any of the following signs continue to occur to a degree that is out of line with developmental stage and that adversely affects social, academic, and occupational activities:

It should be noted that the indications are not limited to oppositional conduct, defiance, animosity, or inability to comprehend duties or directions. At least five signs are necessary for older teenagers and adults (average age 17 and above).

- Frequently ignores specifics or makes thoughtless errors in assignments, at work, or in other contexts (e.g., ignores or misses information, work is wrong).

- Frequently finds it difficult to focus on chores or play activities (e.g., finds it difficult to stay attentive during lectures, talks, or extended reading).

- Frequently appears not to listen when talked to directly (e.g., appears to be distracted, even when there isn’t a visible source of distraction).

- Frequently disregards directions and does not complete assignments, household tasks or obligations at work.

- Frequently struggles with task and activity organization (e.g., struggles with handling sequential tasks; disorderly materials and things; sloppy, disorganized work; has inadequate time management; misses deadlines).

- Frequently shy’s away from, detests, or is hesitant to perform things requiring extended mental effort (such as homework or schoolwork; for older teens and adults, filling out forms, writing reports, and going over long documents).

- Frequently misplaces items needed for jobs or activities (such as school supplies, pens, textbooks, tools, wallets, keys, documents, spectacles, and cell phones).

- Is frequently readily sidetracked by irrelevant stimuli, which, in the case of older adults and adolescents, may include irrelevant ideas.

- Is frequently forgetful when performing regular tasks (such as running errands or doing chores; for older teens and adults, answering phone calls, making payments, scheduling appointments).

(2) Hyperactivity and Impulsivity

At least six months’ worth of six (or more) of the following symptoms have persisted to a degree that is out of line with developmental stage and has a direct detrimental influence on social, intellectual, and occupational activities: It should be noted that the symptoms are not limited to acts of anger, oppositional conduct, defiance, or inability to comprehend duties or directions. At least five symptoms are necessary for older teens and adults (age 17 and above).

- Frequently fidgets, tapping hands or feet, or wriggling in chair.

- Frequently gets up from their seat when it is expected that they stay seated (e.g., leaves their place in the classroom, in the office or other workplace, or in other circumstances that call for staying put).

- Frequently sprints around or climbs in improper places. (Note: In adults or teenagers, it might only refer to restlessness.)

- Frequently unable of playing or partaking in leisure activities in peace.

- Is frequently “on the go,” behaving as though they are “driven by a motor” (i.e., finds it difficult to sit still for long periods of time, such as in meetings or restaurants; others may perceive them as agitated or challenging to follow).c. Frequently sprints around or climbs in improper places. (Note: In adults or teenagers, it might only refer to restlessness.)

- Often talks excessively.

- Frequently answers questions before they are fully asked (e.g., finishing others’ sentences; impatient for a turn in conversation).

- Frequently finds it difficult to wait for their turn, as in a queue.

- Interrupts or bothers people frequently (e.g., butts into games, talks, or activities; may begin utilizing other people’s property without their consent or permission; for adults and teenagers, may trespass or take over other people’s tasks).

Development of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Before the kid turns four years old, it can be challenging to differentiate symptoms from highly varied normal behaviors, even though many parents initially notice excessive motor activity in their toddler. The primary school years are when ADHD is most frequently detected, and at this time inattention becomes more noticeable and problematic. Through early adolescence, the illness is largely stable, although for some people, it worsens with the emergence of antisocial tendencies. Most ADHD sufferers experience less overt motor hyperactivity during adulthood and adolescence, but impulsivity, poor planning, restlessness, and inattention still plague them.

A significant percentage of kids with ADHD continue to have impairments far into adulthood.

In preschool, the main manifestation is hyperactivity. Inattention becomes more prominent during elementary school. Adolescent hyperactivity symptoms, such as running and climbing, tend to be less frequent and may only manifest as fidgeting or an internal sensation of restlessness, impatience, or jitteriness. Even after hyperactivity has subsided in adulthood, impulsivity can still be an issue, coupled with inattention and restlessness.

Risk And Prognostic Factors

Temperamental

ADHD is linked to negative emotionality, increased novelty seeking, and/or decreased behavioral inhibition, effortful control, or constraint. Although they are not unique to ADHD, these characteristics may put some kids at risk for the condition.

Environmental

Less than 1,500 grams at birth indicates a two- to three-fold increased risk for ADHD, however the majority of low-birth-weight children do not go on to have ADHD. While there is a correlation between smoking during pregnancy and ADHD, part of this link may be due to shared genetic risk. Reactions to dietary components may account for a small percentage of instances. There may be a history of child abuse, neglect, multiple foster placements, neurotoxin exposure (e.g., lead), infections (e.g., encephalitis), or alcohol exposure in utero. ADHD has been linked to exposure to environmental toxins, although it is unclear if these links are causative.

Genetic And Physiological

First-degree blood relatives of people with ADHD have higher levels of ADHD. There is a significant heredity to ADHD. Although there is a genetic correlation between some genes and ADHD, this correlation is neither required nor sufficient. Potential factors that may impact symptoms of ADHD include seizures, sleep disorders, metabolic abnormalities, vision and hearing impairments, and dietary inadequacies.

ADHD is not associated with specific physical features, although rates of minor physical anomalies (e.g., hypertelorism, highly arched palate, low-set ears) may be relatively elevated. Subtle motor delays and other neurological soft signs may occur.

Course Modifiers of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

While it is unlikely that early family interaction patterns may result in ADHD, they may have an impact on the disorder’s trajectory or hasten the emergence of conduct issues.

Pathophysiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

According to current models, ADHD may be linked to dysfunctions in some neurotransmitter systems in the brain, especially those that deal with dopamine and norepinephrine. Numerous brain regions receive dopamine and norepinephrine signals from the ventral tegmental region and locus coeruleus, which in turn regulate a range of cognitive functions. The frontal cortex and striatum receive dopamine and norepinephrine pathways, which are directly in charge of regulating motor function, drive, reward perception, and executive functioning (cognitive control of behavior). It is well recognized that these pathways are essential to the pathogenesis of ADHD. Some have suggested a bigger version of ADHD with more pathways.